By William Garcia

Black Lives Matter curriculums emerging all over the U.S

With an increase media attention to police violence there is an emergence of educators utilizing Black Lives Matter as a movement to create and develop curriculums of social justice (Rethinking Schools 2015). The recent article Black Lives Matter: Building-the-school–to-justice (2015) posits that for the past decade, social justice educators have decried the school-to-prison pipeline: a series of interlocking policies—whitewashed, often scripted curriculum that neglects the contributions and struggles of people of color; zero tolerance and racist suspension and expulsion policies; and high-stakes tests that funnel kids from the school to the cell block. But with the recent high profile deaths of young African Americans “a school-to-grave pipeline” is coming to focus. But yet what does it mean to be black in the United States? Am I as an Afro-Latino allowed to call myself Black? Who gets to be African American? Some recommendation from the article was to:

- Provide a social justice anti-racist curriculum that gives the students the historical grounding, literacy skills and space to explore the emotional intensity of feelings around the murder of black youth by black police

- Support students who want to have the conversations on Black Lives Matter outside the classroom in school forums or school clubs.

- Raise the Black lives Matter with other teachers at tour school

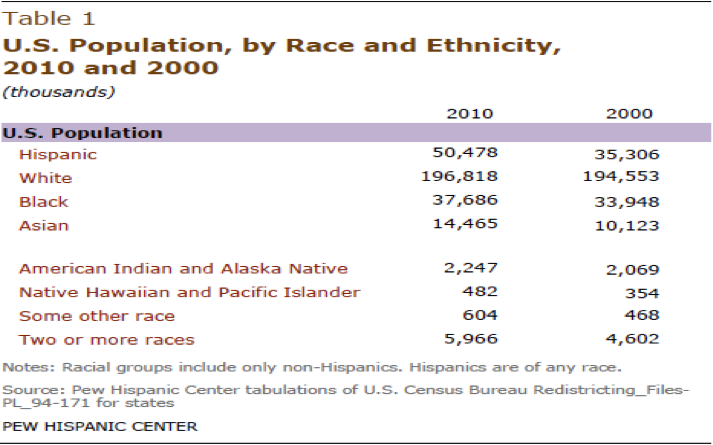

These recommendations do not mention the growing Hispanic population that is also comprised of Afro-Latinos. Afro-Latinos are people of African descent in Mexico, Central and South America, and the Spanish-Speaking Caribbean, and by extension those of African descent in the United States whose origins are in Latin America and the Caribbean (Flores & Jimenez, 2010). According to a recent poll ‘Hispanics’ will be the overwhelming majority in the U.S, yet there is little knowledge of how race, ethnicity, gender and national identity functions under a nomenclature of Latinidad in the U.S. For many, Latinos are all composed of one race and have little differences between us. The one-size-fits-all approach to Latino students is the approach many educators act upon when educating and interacting with their Latino population. When one considers the census categories intended for Latinos—Black Non-Hispanic and white Non-Hispanic—Latinos are denied access into two races and then categorized as an ethnicity.

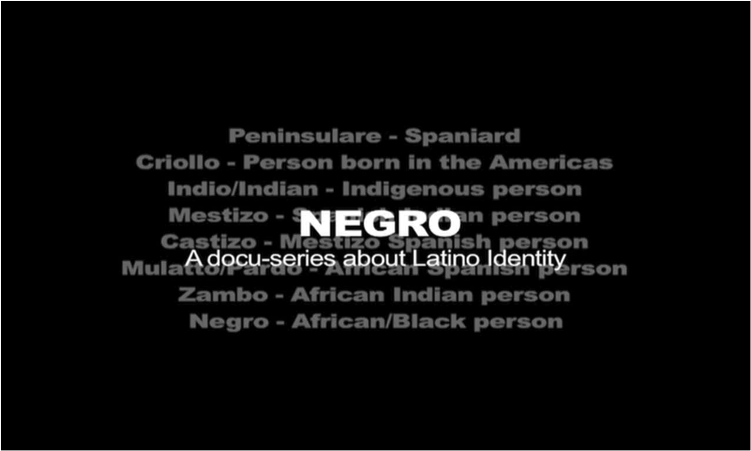

A diverse afro-descended student population mainly from Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America has complicated the topic on what it is to be black in the United States. If All Black Lives Matter, then is being black synonymous with being African American? Can Afro-Cubans or Afro-Colombians be black?

Fixed categories of blackness do not allow Afro-Latinos to identify and explore their identities, which creates an invisibility of how policy, especially in the realm of education, has not been developed to attend to their academic needs. There is a need to redefine what it means to be black in this country. Essentialist forms of blackness in the U.S makes it difficult for students to relate to the way that we can understand race critically and politically as well as teaching in ways that are culturally relevant for them.

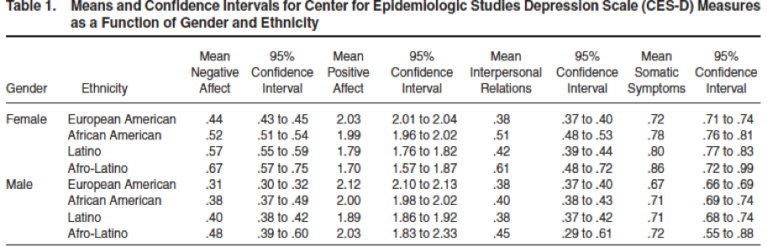

When it comes to the social-emotional condition of Afro-Latino students in the classroom it is clear that they are culturally and racially misunderstood which seems to lead to higher levels of depression in these students. For example, in 2003 an academic article titled: “Dual Ethnicity and Depressive Systems: Implications on Being Black and Latino” indicated that Afro-Latino females tended to exhibit higher levels of depressive symptoms than adolescent males and older adolescents tended to show higher levels of depression than younger adolescents.

- Empirical research on the social and psychological adjustment of Latinos of African decent is virtually non-existent.

- Many adolescents comment were: “People were unfriendly to me”, “I felt that people disliked me”.

- Many Afro-Latinos are faced with a number of stressors associated with their unique dual ethnicity and double minority status.

- Afro-Latinos in therapy mentioned also having distress due to having problems fitting in and gaining acceptance from peers at a time when that is a high priority.

Another article that sheds light on how schools in the United States fail to create curriculums for Afro-Latino students is Ramos-Zaya’s “Learning Affects, Embodying Race: Youth, Blackness, and Neo-Liberal Emotions in Latino Newark” (2011) which concluded in his transnational study that: In Newark and Belo Horizonte (Brazil) only two students identified as black and deployed and Afro-Brazilian pride and solidarity language. As a result, their friends challenged their Black self-identification and simply did not feel these students looked Black and accused the students from Belo Horizonte of identifying as black because it was trendy particularly in light of affirmative actions discussions happening at the times. The Santurce youth felt that it was based on spatial terms, following a “Rastafari” identity or living in Piñones, areas associated with Afro-Caribbean arts and folklore though not with explicit struggles of racial justice and empowerment. Meaning, even when Afro-Latinos identify with their blackness, other students policed and defended established notions of identity.

According to Ladson Billings (1995) cultural relevant pedagogy is characterized as teaching that empowers students intellectually, emotionally, socially and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills and attitudes. This teaching helps black students develop different ways of being black and Latino in a way that helps the students understand themselves and strive for academic excellence. This callous point of encounter of the lack of culturally relevant pedagogy for Afro-Latino students is reinforced with the proliferation of white and light-skin actors in and outside of schools, and across media as such. Telemundo and Univision selling a world of whiteness. All one has to do is go to novela-watching Latino household and you will see family members stuck on the couch in a trance watching novelas (soap operas) throughout the day and whenever possible.

Regardless of these shortcomings, anti-black racism and white supremacy in the Latino media is being confronted. The recent impact of El Proyecto Mas Color is an awareness campaign started by Sophia and Victoria Arzu, two young Honduran-American women of Garifuna descent. Their project promotes the representation of Afro-Latinos and other minorities in Latino media and campaigns for more diverse depictioon Spanish-language television that includes Afro-Latinos and beyond.[1] Furthermore, Victoria Arzu expresses the fundamental and insightful criticism that is disregarded in the Latin@ community: “People need to remember that Latino is not a race”.[2]

Sophia and Victoria Arzu speaking in a YouTube video expressing their concern for the lack of black bodies in Spanish-Speaking media, especially on Telemundo and Univision.

A segment of National Public Radio, was in the forefront of condemning racial injustice in Latino media. In fact, they have written a plethora of letters to Telemundo and Univision television networks requesting the presence of Afro-Latin@s and other minorities.[3]

LETTER TO

Telemundo

Univision Communications

Telemundo

Include more Afro-Latinos in your daily programming, and give them positive roles. Afro-Latinos have been shoved under the rug for too long in the Latino community and the only explanation for this disparity is discrimination. We want to see more Afro-Latinos on your programs because this is the 21st century and it’s time to stop this discriminatory attitude.

Telemundo responded to them by saying that they were unable to fulfill the request because it would compromise ratings and because they were based in Mexico.[4] As a response, they founded Proyecto Mas Color, which has a created a petition against Telemundo and has accumulated almost 100,000 signatures and continues to raise consciousness. Another Video posted by the Arzua sisters, “What Am I (Afro-Latino)” discuss what it is to be Afro-Latinos and confronted the assertion all black people are African Americans. As young students they are an inspiration for other Afro-latino students who seek visibility and agency. These initiatives have successfully had an impact on a political level. In September 2014, during Spanish Heritage month, the AfroLatin@ Forum organized a roundtable discussion in New York City to appeal to the U.S Census Bureau to re-analyze the account of their numbers and recognize Afro-Latino identities.

Curriculum manifests cultural sensitivity, varying perspectives, and authenticity, controversial topics are addressed proactively and teachers clarify any biases in the material. An effective Afro-Latino centered pedagogy legitimizes:

- Afro-Latin American forms of knowledge through shared experiences with African Americans and other afro-descendants (e.g. Civil Rights, Hip-Hop, U.S imperialism).

- Scaffolds cultural practices that are part of their identities and communities.

- Extends and build their native languages (Garifuna, Spanish, Spanglish)

- Reinforces community ties with ones race, nation, gender and experiences in the U.S

- Promotes positive social relationships with other afro-descendants in the U.S in ways that encompasses unity through difference.

- Creates an Afro-Latino self-determination and self-worth (socio-emotional)

- Promotes cultural and critical consciousness

In closing, I propose a rich theoretical understanding on Afro-Latino student development based on critical race theory, culturally responsive pedagogy and practice. Addressing racial disparities is about engaging students thereby making their lives better. I believe that creating Afro-Latino pedagogy will create a community of practice in which inquiry is a cornerstone of continuous student self-re-definition through improvement in culturally responsive systems. Black students in the United States are commonly referred to as simply African American without taking into account Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino students. I believe that an action-based research on Afro-Latinos requires having an understanding of becoming culturally responsive. We need educators to get involved with Afro-Latino students, our history and the way we occupy space in the Americas in order to address this gap in education.